🏙 Marketplace city expansion strategy

Most of the marketplaces I looked at took 8 to 12 months post-launch to expand into their next market. A few marketplaces, like Caviar and OpenTable, launched their second and third markets at essentially the same time...

How marketplaces like Instacart, OpenTable, Caviar, Grubhub, and others approached expanding into additional markets

Q: How do marketplaces expand from a single market to new markets? When should we expand, how do we pick which markets to expand into, and do you have any other advice for how to launch in a new market?

The early days of new marketplaces fascinate me. There’s so much work happening, all so manual, and most of the time you have no idea if what you’re doing will keep working if you stop doing-things-that-don’t-scale. If you’re lucky, though, eventually, you start to see the beginnings of a flywheel—customers reliably have a good time, supply sticks around, and successful transactions happen reliably without hand-holding. The marketplace starts to work!

Around this time, being an ambitious founder, you start to wonder: Is now the time to expand into a second market? Expand too early and risk both markets failing. Expand too late and you give your competition a chance to race ahead.

To help you through this critical decision, I polled the founders and early growth leads at some of today’s biggest marketplaces and asked them a bunch of questions:

- How long did it take you to expand into a second market?

- When did you decide it was time to expand?

- How did you pick which markets to expand into?

- What did your launch team look like?

- What did a launch playbook look like?

Below are their stories.

A HUGE thank-you to these wonderful people who so generously shared their insights with us: Casey Winters (Grubhub), Kevin Tan (Snackpass), Max Mullen (Instacart), Mike Xenakis (OpenTable), Matt Bendett (Peerspace), and Nat Emodi (Caviar) 🙏

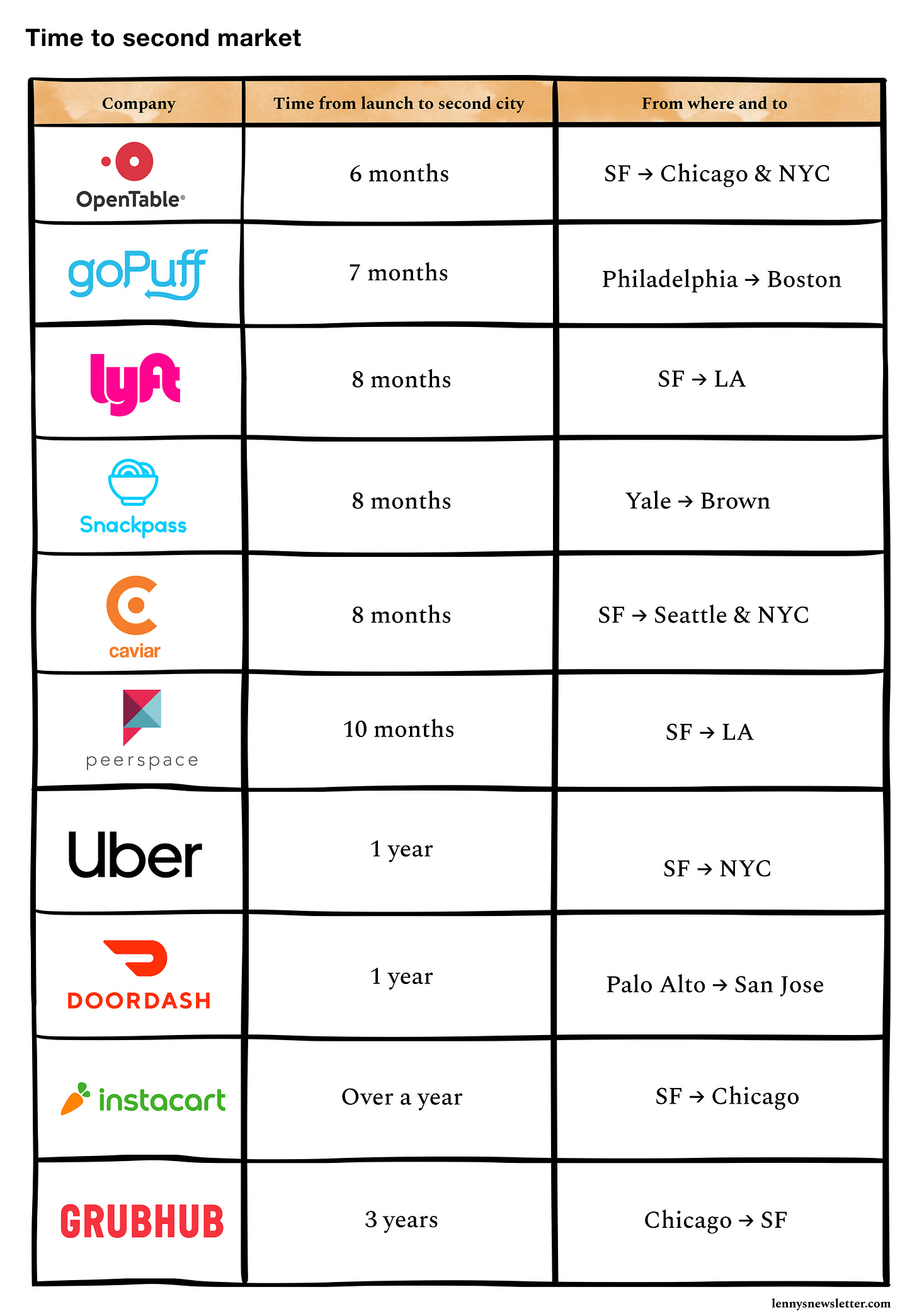

How long did it take to expand into a second market?

Most of the marketplaces I looked at took 8 to 12 months post-launch to expand into their next market. A few marketplaces, like Caviar and OpenTable, launched their second and third markets at essentially the same time (to get ahead of competition), and interestingly, all of these marketplaces expanded to a small set of early markets: SF, NYC, LA, Chicago, Seattle, and Boston.

As you’d expect, the time prior to expansion was spent finding product-market fit and figuring out how to make the marketplace work within a single, constrained market. e.g. OpenTable:

“The first six months were spent getting product-market fit with the initial installs in SF (the founder sitting with the software in the restaurants).”

—Mike Xenakis, former SVP at OpenTable

Bottom line: Expect to expand to your second market in under a year after launch, and (considering how quickly markets grow these days) likely much sooner.

When should you expand to a second (and third) market?

As soon as your first market starts to work.

Why not sooner?

“It’s much easier to focus sales in a geographically concentrated area (e.g. neighborhood) than to take a scattered approach. Twenty restaurants highly concentrated was much better than 30 restaurants spread out.”

—Mike Xenakis

For some marketplaces, this meant hitting a meaningful milestone that told them the market was working:

“We were ready to expand to Chicago when we nailed operations in SF and built the tools to actually launch another city. This actually required breaking all kinds of fundamental assumptions that were hard-coded at the time.”

—Max Mullen, co-founder of Instacart

“Once we saw the reception in SF, we knew the idea was something that had traction. The specific milestone that convinced us of product-market fit was 100 average daily orders.”

—Nat Emodi, early GM at Caviar

“Our first market had extremely high product-market fit. Engagement (orders per week) and retention were high, and over 90% of new users came from friends telling their friends.”

—Kevin Tan, CEO of Snackpass

For others, they finally had a launch playbook they were confident in:

“We expanded once we had a playbook to make a market successful, and the resources weren’t fully absorbed in executing the market expansion playbook in our first city.”

—Casey Winters, former head of growth at Grubhub

Or they wanted to demonstrate they could make a new market work ahead of an upcoming funding round:

“We wanted to show we could transfer our nascent operational playbook to another large market, taking what we learned in our home market to one we thought had a larger opportunity for growth.

We also wanted to demonstrate we could repeat the growth trajectory in multiple markets prior to our Series A raise. This is hard to do when your team is small and resource-constrained. Not all went according to plan because we hadn’t really understood our market model benchmarks at the time. But I’m glad we went for it anyway, because it accelerated the pace of learning.”

—Matt Bendett, co-founder of Peerspace

In highly competitive markets (e.g. convenience-store delivery today), it’s even simpler: expand as quickly as humanly possible. This was the case with OpenTable:

“When thinking about city expansion, you need to consider the model being employed by every internet startup in 1999—grab as much land as possible. There was a false assumption that capital was endless, so everyone emphasized a first-mover advantage investment, and OpenTable was no different. In the case of OpenTable, there was another element in play: Dining is local. It was conceivable that a competitor could own a given city even if they were a small player. Therefore, there was a rush to get everywhere as fast as possible.”

—Mike Xenakis

And with Caviar:

“There was a general conviction that the last-mile delivery model was the future, so we needed to have a first-mover advantage in major cities.”

—Nat Emodi

And even more-so with newer marketplaces like Jokr, which from what I understand launched in three markets immediately.

Bottom line: Expand into a second market as soon as you feel like your first market is working, you have a semblance of a playbook, and the resources to do it. If, however, you’re in an extremely competitive environment (and have a lot of VC money), it may make sense to be more aggressive.

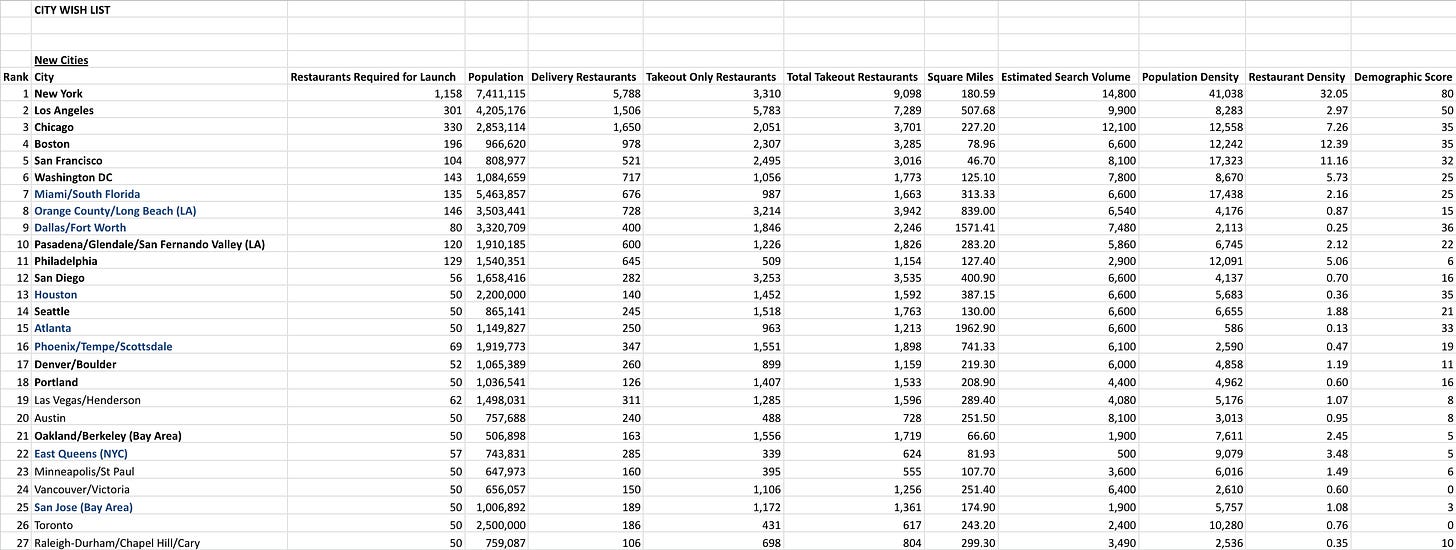

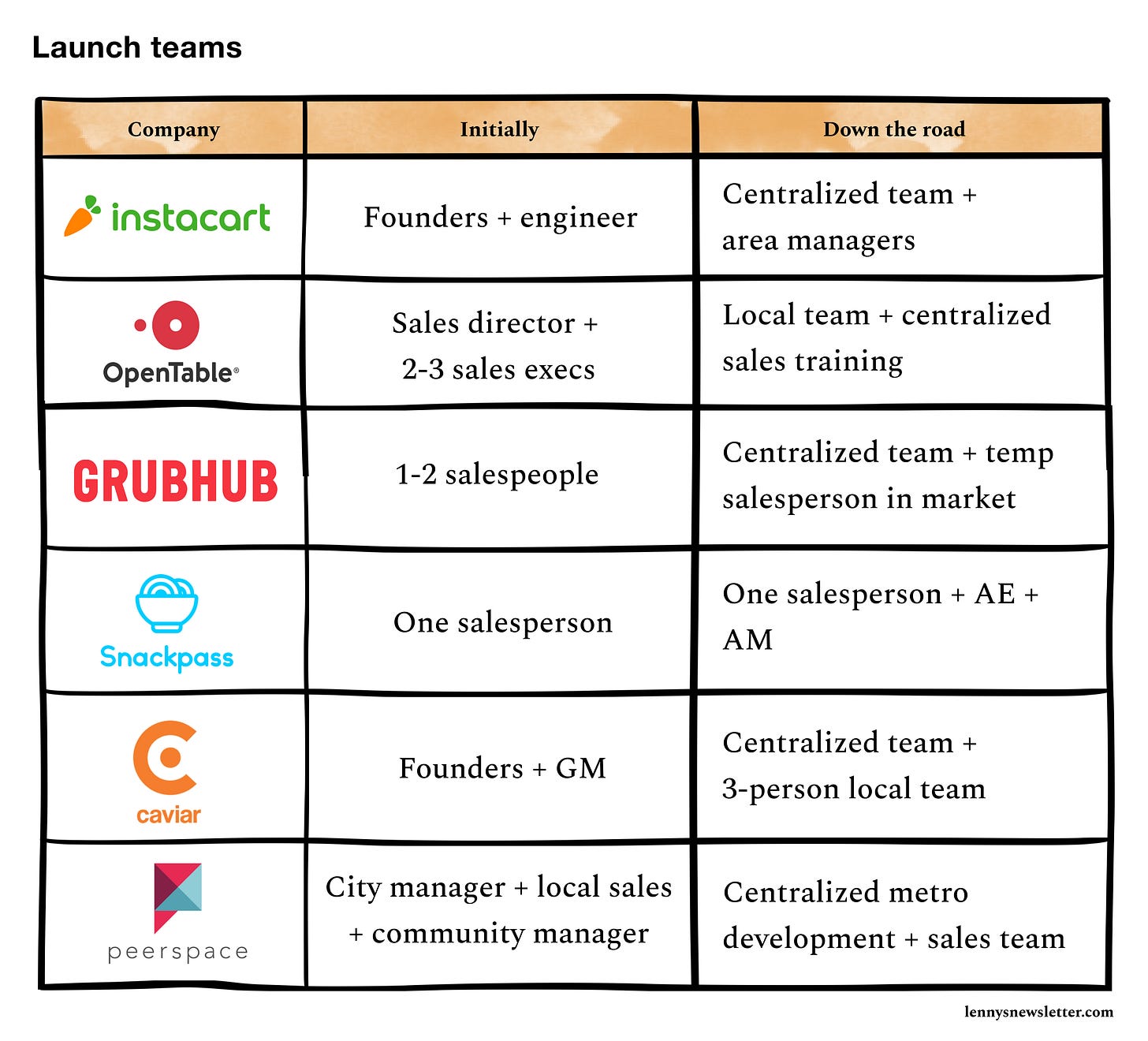

How do you pick which markets to expand into?

Create a spreadsheet with 3 to 5 attributes that tell you whether a city will be a good fit, and then stack-rank them. For example, here’s Grubhub’s early spreadsheet (courtesy of Casey Winters):

“I built a spreadsheet that mapped population, population density (less likely to have cars and drive to get food), delivery restaurants (restaurants had to do their own delivery), search volume for delivery keywords on Google, and a demographic score we used from census data mapped into a piece of software called Maptitude (trying to find young professionals).”

—Casey Winters

Here’s a rough breakdown of what each of these marketplaces put in their spreadsheet:

In addition to city size and demographics, Instacart also looked at waitlists in unlaunched cities (“emails we’d collected from people who tried to sign up from those cities”), whether there was a startup community (“a sign that there were early adopters who would help us with word of mouth”), and the physical layout of the city:

“Every city has unique characteristics. For example, NYC requires a different logistics algorithm that accounts for some deliveries happening on foot. LA is subject to sprawl, so there are multiple zones in that metropolitan area. Chicago, on the other hand, launched as one big zone, similar to how we operated SF at the time.”

—Max Mullen

Caviar and OpenTable looked closely at the food culture of the city:

“On the qualitative side, a judgment call on how much of a ‘foodie’ city it was, backed up by awards, reviews, and word of mouth.”

—Nat Emodi

“You could take the Zagat guide and quickly establish the most important dining cities in the U.S. Ultimately, it reflected the major metropolitan cities like SF, DC, Chicago, NYC, LA, etc.”

—Mike Xenakis

Peerspace looked at the city’s interest in art and entertainment:

“We looked at GDP and population density, but also unique customer criteria including creative industry economies and discretionary income spent on entertainment by market.”

—Matt Bendett

And Snackpass segmented its markets into archetypes:

“We chose several market archetypes: college towns, suburban/rural, and urban. By having multiple archetypes rather than the same, we gained confidence that Snackpass would succeed beyond one type of market.”

—Kevin Tan

Bottom line: Alongside population size and density, determine which 2 to 3 attributes tell you a market is ideal for your marketplace, throw your best guesses into a spreadsheet, stack-rank your options, and iterate from there.

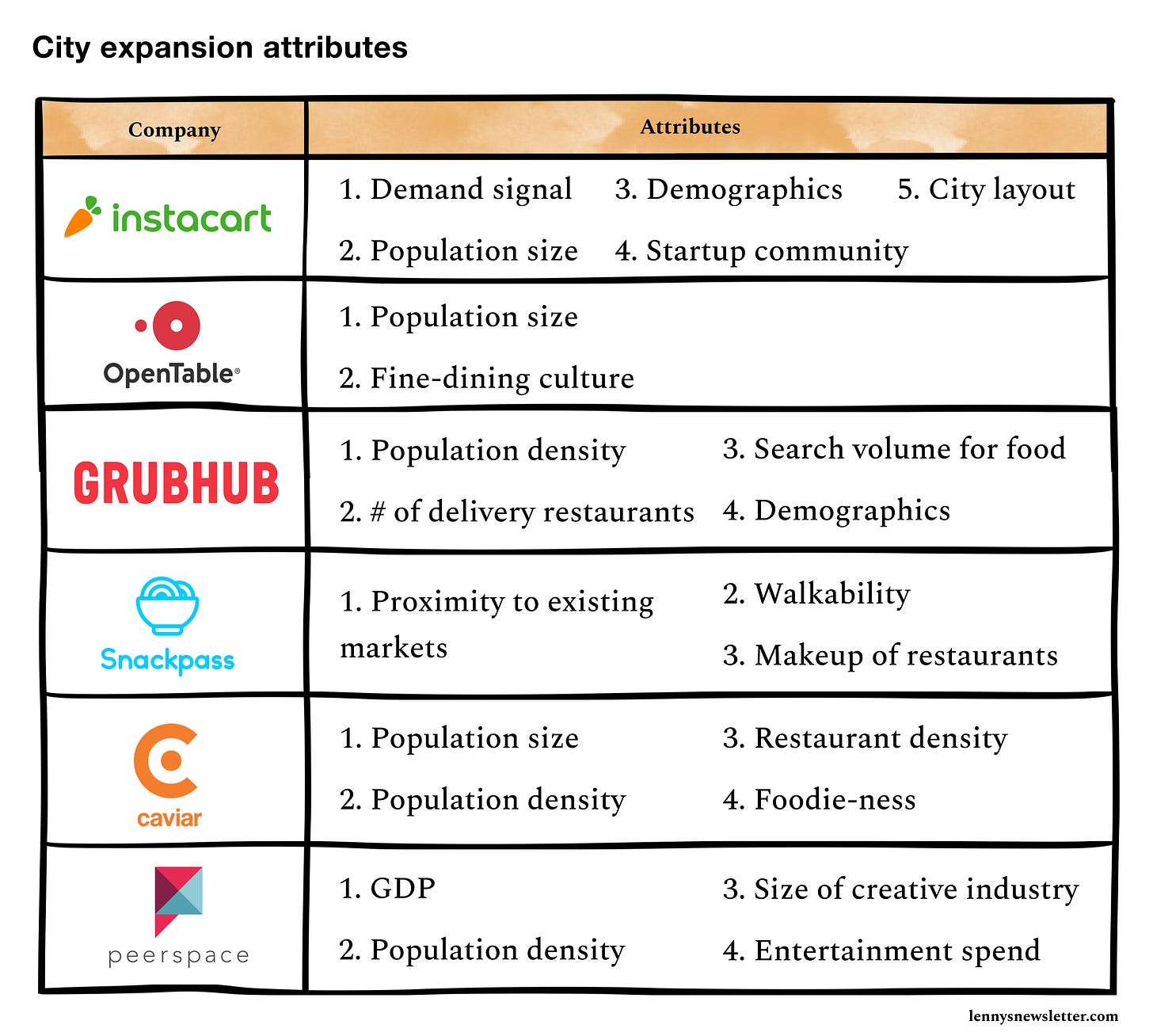

What should your launch team look like?

Here’s a breakdown of what launch teams look like, initially and down the road:

In general, launch teams across the board were very small, primarily salespeople. For example, OpenTable:

“The launch team involved a sales director and usually one or two other sales execs. They would land in a city and set up shop for a month. During that time, they would hire a local sales exec and an operations manager.

Together the team would make the initial push to get 20 restaurants signed. Once up and running, the launch team would move on to the next city.

Keep in mind that our sales process was labor-intensive (i.e. knocking on doors) and was coupled with a heavy lift on the operations side (installing our system). Eventually we moved away from a launch team and simply moved to a standard market-opening process that involved hiring a local team, bringing them to HQ for significant training, and then turning them loose to drive the market growth. There was no longer a launch team to fly around the country.”

—Mike Xenakis

And Snackpass:

“For us, it was essential to have people on the ground who understand the local nuances—which restaurants moved the needle, what were the customer experience issues, etc.

In the beginning we had one restaurant-facing launcher per market, while user growth was a centralized team. We still use this model but added in an AE and AM distinction on the restaurant side.”

—Kevin Tan

For a few marketplaces, the founders were intimately involved with city launches, who then recursively hired and trained new teams to launch additional markets, e.g. Instacart:

“At first, we as founders launched new cities with a few early engineers to build the tooling on the ground.

Then, we trained a set of ‘city launchers’, who then cross trained new launchers in subsequent launches. That allowed us to launch multiple cities in parallel.

Eventually the city launch function was centralized into an expansion team based in SF that would launch each city, hire local Area Managers and then move on to the next launch.”

—Max Mullen

And Caviar:

“The initial launch team was the Caviar co-founders plus local GMs. This evolved into three-person local teams that would launch a market with support from a central launch team.

Our local teams would focus on restaurant sales and courier operations, and the central team would drive marketing, press, customer support, and other functions.”

—Nat Emodi

Everyone I talked with eventually converged on a central team running demand growth alongside an inside-sales team supporting supply growth:

“Early on, we’d send a salesperson or two into the market to sign up restaurants and hire a local salesperson. They would sign up 50 restaurants, train up the local salesperson, and leave the local salesperson to execute against their quota.

On the demand side, I would create landing pages and Adwords campaigns for all of the neighborhoods and cuisines we covered, get them indexed for SEO, bid on Adwords for the ones that had four or more restaurants, and reach out to some local bloggers and tell them about the launch to get some inbound links. After a while, we figured out we didn’t need to hire a local salesperson. We could just send a salesperson for a couple weeks, have them get 50 restaurants, and then hire an inside salesperson in HQ to continue to grow supply in the market. I hired a dedicated search engine marketer who automated a lot of these workflows as part of the job of owning all of our SEM spend. We had a city launch manager for a little while once we started doing a lot of them. I don’t think it helped much.”

—Casey Winters

Same story with Peerspace:

“Early on, we set up shop in each market. That consisted of an office, a city manager, a supply acquisition specialist (possibly more than one), and a community manager to drive local awareness and host loyalty.

We built intangible value this way, as our legacy markets suggest now, but the effort wasn't scalable, nor was it a pathway to profitability that a company needs with limited runway.

Over time, we focused more energy on a repeatable launch playbook and growth forecast so we could add supply quickly and monitor markets to see how they performed.

We added a Metro Development function to review performance and prioritize markets that needed triaging or doubling down on. We went from highly customized to centralized. In retrospect, the real answer is somewhere in the middle, and our playbook adapts depending on the market opportunity and how much of a cold-start problem we have ahead of us.”

—Matt Bendett

Bottom line: Start small and sales-driven.

What does a launch playbook look like?

Instead of summarizing these playbooks, I present the high-level playbooks shared with me in their full glory:

Grubhub’s early city-launch playbook (credit: Casey Winters):

- Maintained the city expansion spreadsheet to determine the next target markets. As part of annual planning, figure out our capacity for new markets and put them into the plan.

- Once ready to launch a market, send paratrooper(s), i.e. salespeople, into the best neighborhoods for two weeks, get 50 restaurants to sign up. Only pay when you receive an order, cancel anytime, no hidden fees.

- Hire a local salesperson (early) or staff an inside salesperson with the new territory (later) to continue to grow supply.

- We knew restaurants gave us a few months to prove we could drive demand, so this starts the clock for the demand-side growth team (read: me) to start generating order volume. The first step was to get the restaurant’s page live. The SEO/SEM landing pages would show the restaurants available for any geo and cuisine combination, e.g. “Nob Hill Thai delivery,” “94107 food delivery.”

- Start bidding on Adwords for the keywords where we had 4+ restaurants that matched the term, because at that point, we would have a decent enough conversion rate and could hit expected CAC targets (which were based on a six-month payback period).

- Email local bloggers in the market and tell them we are about to launch. Offer their readers $10 off their first order by going to our market launch landing page.

- Once the promo expired (after 30 days), redirect that landing page to the market SEO landing page to develop page/domain authority.

- Continue to sell into the market, driving conversion and retention improvements on the demand side. Once we hit certain targets there, it would open more demand-side growth efforts, e.g. transit advertising.

- The VP of sales and I review zip-code-level reports of supply and demand for all markets every month to help focus our teams on driving better liquidity in the right areas.

OpenTable’s early city-launch playbook (credit: Mike Xenakis):

- Establish a target list of restaurant influencers—the restaurants that others in the city would follow if they saw them using a new solution.

- Sponsor some local restaurant information-gathering sessions.

- Sell hard on the value of the software as a much better way to run a restaurant. We had a low emphasis on the online demand piece in the early phase of market development.

- Leverage SEO and restaurant websites as the biggest driver of demand. After going public, we began investing more in SEM as well.

- Watch the network effect take root. More restaurants led to more diners, which led to more restaurants.

Snackpass’s early city-launch playbook (credit: Kevin Tan):

- Build initial supply—namely, whale restaurants.

- Secure content such as promotions and rewards.

- Market content to the user base and turbocharge this with tactics such as social media events, ambassadors, and other types of field marketing.

Peerspace’s early city-launch playbook (credit: Matt Bendett):

Supply is king:

- Get the market seeded and initially curated with variety that exemplifies your unique offering.

- When we hit a certain threshold, marketing components would kick in, some automatically and others manually.

- Our goal was to amplify this in many areas at once, so we staffed up our supply ops team but kept the spend efficient and time-to-payback (with fully allocated OpEx) quantifiable. Seeding markets after we anchored our mature metros really made a difference.It took a lot of trial and error on different playbook approaches before we settled on something that worked for us. We considered the wealth of data we had access to but chose to keep the KPIs simple (examples): supply benchmark required by vertical, booking targets necessary to sustain growth, leading indicators like searchers per listing, % utilization of available inventory.

Getting the markets comparable to one another allowed us to determine where Ops resources and marketing budget needed to be allocated.

Caviar’s early city-launch playbook (credit: Nat Emodi):

- Identify the part of town with the highest density of restaurants and most affluent customers.

- Focus disproportionate effort on signing up major “market maker” restaurants that were super-popular among locals and had limited or no delivery.

- Once we got a few of these, it was a matter of very quickly ramping up consistent courier coverage to ensure fast deliveries, and customer support to ensure high CSAT. These both had a direct correlation on a market’s early retention metrics.

In summary

- Time it takes to expand into a second market: Average is 6-8 months.

- When it’s time to expand: As soon as you feel like your first market is working, have a semblance of a playbook, and have the resources to do it.

- How to pick the next market: Create a spreadsheet with 3-5 attributes that tell you a city will be an ideal fit for your marketplace, and then stack-rank them.

- What an early launch team looks like: Small and sales-driven.

Again, a HUGE thank-you to Casey Winters, Kevin Tan, Max Mullen, Mike Xenakis, Matt Bendett, and Nat Emodi.